Lafayette Chapter

Kentucky Society - Sons of the American Revolution

Color Guard Flags

|

United States of America The National Flag of the United States of America is often referred to as the American flag. It consists of thirteen horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white stripes. The canton contains a blue rectangle (referred to specifically as the “union”) bearing fifty white, five-pointed stars arranged in nine offset horizontal rows. The 50 stars on the flag represent the 50 states of the United State of America and the 13 stripes represent the original thirteen British Colonies that declared independence from Great Britain and became the first states in the Union. The 50 star flag was adopted and flown for the first time ever at Fort McHenry on the Fourth of July in 1960. This version of the American Flag is the longest to serve as the National Colors of the United States of America. |

|

Grand Union The Grand Union Flag, also known as the Continental Colors, has been generally regarded as the true “first flag” of our nation, but was never recognized by Congress as an official flag. It consists of a field of thirteen stripes, just as our flag today, combined with the British Union flag. The British Union was used in the flag because at the time the colonists still considered themselves British citizens as independence had not yet been declared. The Grand Union flag was first flown on the first flagship in the Continental Navy, the Alfred, in Philadelphia on 2 December, 1775, by Lieutenant John Paul Jones. Letters written to Congress verify this event. The Grand Union flag was used by the American Continental forces as both a naval ensign and garrison flag through 1776 and early 1777. It served as the flag of the Revolution until it was replaced in a declaration of the Continental Congress on 14 June, 1777. |

|

Francis Hopkinson The Stars and Stripes originated as a result of a resolution adopted by the Marine Committee of the Second Continental Congress at Philadelphia on 14 June, 1777. The resolution read:

Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was responsible for the earliest design of the Stars and Stripes. At the time that the flag resolution was adopted, Hopkinson was the Chairman of the Continental Navy Board’s Middle Department. Hopkinson also helped design other devices for the Government including the Great Seal of the United States. The evidence supporting Hopkinson as the designer of the first Stars and Stripes Flag is a series of letters and bills submitted by Hopkinson to various government agencies requesting payment for his work in designing the flag. Due to bureaucracy and political enemies, Hopkinson was never paid for his design. Though Hopkinson’s political adversaries blocked all attempts to have him paid for his services, they never denied that he made the design. Furthermore, the journals of the Continental Congress clearly show that he designed the flag. It is believed the design of the first Stars and Stripes by Hopkinson had the thirteen stars arranged in a staggered pattern technically known as quincuncial because it is based on the repetition of a motif of five units. In a flag of thirteen stars, this placement produced the unmistakable outline of the crosses of St. George and of St. Andrew, as used together on the British flag. Whether this similarity was intentional or accidental, it may explain why the plainer fashion of placing the stars in three parallel rows was preferred by many Americans over the quincuncial style. Because the original stars used in the Great Seal designed by Hopkinson had six points, it is believed the Hopkinson flag also had six pointed stars. This is supported by his original sketch that showed asterisks with six points. This flag was first carried in battle at Brandywine, Pennsylvania, in September 1777. It first flew over foreign territory in early 1778, at Nassau, Bahama Islands, where Americans captured a fort from the British. |

|

Betsy Ross The Betsy Ross flag is an early design of the United States flag, popularly attributed to Betsy Ross. The flag uses the common design of alternating red-and-white stripes with five-pointed stars in a blue canton. The flag was designed during the American Revolution and features 13 stars to represent the original 13 colonies. The distinctive feature of this flag is the arrangement of the stars in a circle. The date for the first appearance of this flag is unknown, however it is known to have been in use in 1777. Although this early American flag is commonly termed “the Betsy Ross flag” her actual involvement in its development is highly suspect. The main reason historians and flag experts do not believe that Betsy Ross designed or sewed the first American flag is a lack of historical evidence and documentation to support the story. Betsy Ross’ story was first published in 1870, 34 years after her death, by her only surviving grandson. Many historians agree that Betsy Ross probably didn’t design the first American flag, but for more than a century Americans have accepted the story as history. It is worth pointing out that while modern lore may enhance the details of her story, Betsy Ross never claimed any contribution to the flag design except for the five-pointed star, which was simply easier for her to make. |

|

Star Spangled Banner This Flag became the Official United States Flag on 1 May, 1795 and remained so for 23 years until 1818. The addition of two stars and stripes for the admission of Vermont (the 14th State on 4 March, 1791) and Kentucky (the 15th State on 1 June, 1792) gave this flag its 15 stars and 15 stripes. It is the only official flag of the United States with more than 13 stripes. The Star-Spangled Banner (or the Great Garrison Flag) was the garrison flag that flew over Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor during the naval portion of the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. Seeing the flag during the battle inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry”, which, retitled with the flag’s name of the closing lines of the first stanza and set to the tune “To Anacreon in Heaven”, later became the national anthem of the United States. |

|

Great Star In 1817, the Star Spangled Banner, with its fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, was still in use as it had not been updated to reflect the five new states which had joined the union since 1795. The Great Star flag was designed in 1817 by Captain Samuel Chester Reid, United States Navy, at the request of Congressman Peter H. Wendover of New York. Wendover asked Reid to design a flag that would allow for the increase of the number of states without destroying the distinctive character of the flag. He was mainly concerned that the committee appointed to investigate new flag designs was considering increasing both the stars and the stripes. Reid recommended that the stripes be reduced to thirteen for the original states, and that the number of stars representing the whole number of states be formed into one great star on the canton with a new star added with each new state. The Congressional Committee adopted both his 13 stripes idea and the idea of adding a star |

|

Commonwealth of Kentucky The history of the official Kentucky State flag dates back to 1918 when the Generally Assembly authorized a Kentucky state flag. The original flag was designed by Jesse Cox, an art teacher in Frankfort, Kentucky. The design was then not officially authorized until 1928. In 1920 at Camp Zachary Taylor, the first official flag was presented. The flag was not to the standards expected and was sent to a group of artists in Louisville for improvements. Three designs were created and sent to the Governor but were eventually lost. In 1961 the Kentucky Legislature finally authorized the specifications including the design and colors for the State’s flag. An artist named Harold Collins created three designs for the flag. His chosen design was similar to the original design of Jesse Cox. The seal depicts two friends embracing. Popular belief claims that the buckskin-clad man on the left is Daniel Boone, who was largely responsible for the exploration of Kentucky, and the man in the suit on the right is Henry Clay, Kentucky’s most famous statesman. However, the official explanation is that the men represent all frontiersmen and statesmen, rather than any specific persons. The state motto: “United We Stand, Divided We Fall” circles them. The motto comes from the lyrics of “The Liberty Song”, a patriotic song from the American Revolution. |

|

Culpeper The Culpeper Flag was first used in 1775 and was the standard of a group of militia men from Culpeper County, Virginia. The Culpeper Minutemen were formed in July 1775 in response to the growing British threat. They were attached to the First Virginia Regiment, led by Colonel Patrick Henry, who is most famous for his statement, “Give me liberty or give me death!”. The flag features the familiar rattlesnake symbol, the warning, “Don’t Tread On Me”, and the inspiring words of their leader, Colonel Patrick Henry. The rattlesnake, which is found only in North America, became a symbol for the colonies as a result of an article and cartoon published by Benjamin Franklin in 1751. The Culpeper Minutemen were first called into duty when Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, confiscated the colonist’s gunpowder at the Virginia capital, Williamsburg. The colonists were alarmed and Patrick Henry immediately sent word to Culpeper County. The Culpeper Minutemen met at the Culpeper Courthouse carrying their flag and marched for Williamsburg. Sixteen-year old Philip Slaughter, who fought with the Culpeper Minutemen, described the Culpeper flag in his diary as follows:

Philip’s diary provides definitive proof that the Culpeper Flag was in fact carried by the Culpeper Minutemen. This makes the Culpeper Flag somewhat unique because many of the flags considered to be “historic American flags” cannot definitively be linked back to the time of the American Revolution. |

|

Fort Moultrie The Liberty flag (later known as the Fort Moultrie flag) was designed by commission in 1775 by Colonel William Moultrie to prepare for war with Britain. In South Carolina the crescent on the flag was a symbol of resistance to tyranny dating back to the South Carolina protest of the Stamp Act of 1765. Colonel Moultrie’s regiments also wore blue uniforms with a silver crescent on their caps with the words “Liberty or Death”. The flag was first flown in battle when South Carolina Militia under the command of Colonel Moultrie repulsed a British naval attack from Fort Sullivan in Charleston Harbor on 28 June, 1776. Many historians agree that this was one of the most decisive battles of the Revolution. The Liberty Flag was shot away during the battle, but Sergeant William Jasper ran out in the open and raised it again. Sergeant Jasper’s bold action had a rallying effect upon his fellow troops. This dramatic event, along with the pivotal role of the battle itself, earned the flag a place in the hearts of the people of South Carolina, as well as establishing it as a symbol of liberty in the South. It was later renamed the Fort Moultrie flag and became iconic to the Revolution in the South. The South Carolina militia adopted the flag as their standard and with the liberation of Charleston, on 14 December, 1782, it was presented by General Nathaniel Greene’s Southern Continental Army as the first American flag to be carried in the South. |

|

1st Pennsylvania Regiment of Riflemen The flag of the 1st Pennsylvania Militia Riflemen can be traced to the beginning of 1776 when General Washington ordered that each regiment should be furnished with its own colors and that those Colors should bear some kind of similarity to the uniform of the regiment to which they belong. A contemporary description of the flag was provided in a letter written on 8 March 1776 by Colonel Edward Hand. This letter was written from the regiment’s camp outside Boston to Jasper Yeates of Lancaster. The description states:

The letters at the top of the flag stand for “Pennsylvania Militia 1st Regiment”. The Latin motto “Domari nolo” translates to “I Refuse To Be Subjugated”. The Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment was formed on 22 June 1775 from nine companies of Pennsylvania German and Scots-Irish volunteers. Their standard weapon was the longrifle with which they were considered expert marksmen. When the regiment was reorganized on 1 January 1776, it became the First Continental Regiment of the Continental Army. As the First Continental Regiment, they were the first American regiment to be raised, equipped and paid directly by the Continental Congress. The 1st Pennsylvania Riflemen Regiment served throughout the duration of the American Revolution from 1775 to 1783, participating in the siege of Boston, the New York Campaign, Battle of Trenton, Second Battle of Trenton, Battle of Princeton, Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Matson’s Ford, Battle of Germantown, Battle of Monmouth, Battle of Springfield, and Battle of Stony Point. Two companies of the regiment participated in Benedict Arnold’s Quebec Expedition. Colonel Thomas Robinson, received the flag at the end of the war when the First Pennsylvania was mustered out of service in November 1783. On 27 May, 1874, the flag was loaned to the National Museum at Independence National Historical Park by Mr. William S. Robinson, who was a grandson of Colonel Robinson. It was displayed at Independence Hall during the Centennial Exposition of 1876. In December 1879, William S. Robinson sold the flag to the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The flag is still owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and is currently at the William Penn Memorial Museum. |

|

Bennington The Bennington flag is one of the more popular flags associated with the American Revolutionary War. It derives its name from the Battle of Bennington on 16 August, 1777, where, according to tradition this flag was flown. The flag is distinctive because of the large “76” in the blue canton. The flag has the familiar 13 stars and 13 stripes, but in a very different pattern from the other striped flags in that the white stripes are on the outside. The stars have seven points, which was common for flags in the colonial period. The flag is also distinctive because the canton (the blue section) is longer than usual, being 9 stripes deep, instead of the more familiar 7 stripes. The origins of this flag are in question, but it is known that the earliest date the flag could have been made is about 1810. This date is established from the fabric of the flag that is machine-made cotton, which did not exist at the time of the Revolution. The construction of the fabric as having been made on a mechanical loom has been verified both by the Museum of American Textile History in Lowell, Massachusetts, and by Grace Cooper of the Smithsonian Institution. The original Bennington flag is also much too large to have been carried into battle. It is of a size that would more likely be flown in a stationery position over a fort or some similar site. This at least indicates that the flag was probably not used in battle as tradition claims. While the Bennington Flag was not present at the Battle of Bennington, it is nonetheless intriguing as to when was it made and for what purpose. |

|

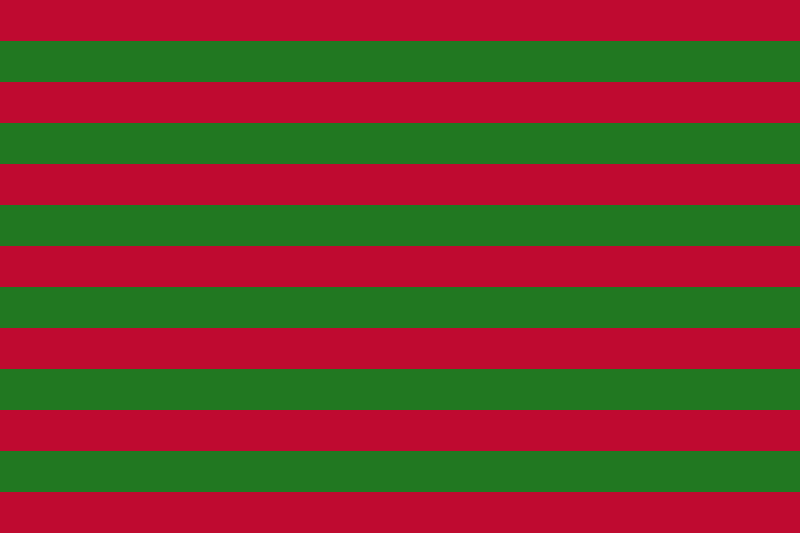

George Rogers Clark The George Rogers Clark Flag is a red and green striped banner in the model of American Flags commonly associated with George Rogers Clark, although Colonel Clark did not campaign under these colors. The “Clark” flag was made in Vincennes, Indiana, and likely flew over Fort Sackville even before Clark arrived. On 12 November 1778, Vincennes resident and general store operator Francois Bosseron recorded the making of the flag for Captain Leonard Helm serving in Clark’s Illinois Regiment. Bosseron records the following items under the heading: “1778 fournie au Capne Helm pour les Compagne des Etats”:

Of all the flags which may have been used during Clark’s Illinois campaign, the 13 striped red and green flag is the only one historically documented, and was one of the first “American Flags” flown in the modern State of Indiana. This flag has been flown by Indiana National Guard units deployed in both Iraq and Afghanistan and is often flown at events in Indiana and Illinois to represent Clark’s historic ties with those states. The red and green flag is still flown at the George Rogers Clark National Historic Park, and at the Locust Grove plantation near Louisville, Kentucky, where George Rogers Clark died. |

|

Cowpens (North Point) The Cowpens Flag, according to legend, was carried at the Battle of Cowpens on 17 January 1781, where American General Daniel Morgan won a decisive victory against the British in South Carolina. The battle was the second of three battles in the south that lead to the eventual American victory in the Revolution. However, there is some controversy about whether the “original” flag currently stored in the Maryland State Archives was at the Battle of Cowpens. Some believe the flag was first flown at the Battle of North Point in the War of 1812, therefore it is also known as the North Point flag.

|

|

Guilford Courthouse The Guilford Courthouse flag is the name given to a North Carolina militia flag which according to tradition was flown at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on 15 March 1781. The flag is easily identified by the reversed colors normally seen on American flags: red and blue stripes in the field with eight-pointed blue stars on an elongated white canton. The original flag has been preserved since 1914 in the collection of the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh, North Carolina. The dimensions of the flag deviate from the standard ratio which gives it a longer appearance. The stars are 8 inches in diameter and have eight points. It is considered the oldest surviving example of an American flag with eight-pointed stars. The actual date of the flag is uncertain as the flag is made of cotton fabric, which was not available for flag making before 1790. Some speculate that Nathaniel Fillmore, who was a veteran of the Revolution, made it during the War of 1812 as a call-to-arms. Others suggest that it was made to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1826. And some, including the Smithsonian have proposed that it could have been made as late as 1876, to celebrate the Centennial. |

|

Kentucky’s River Raisin Battle Flag There is little historical documentation relating to this flag. It is not known when it was first designed or how long it was used. This battle flag was captured by the British in 1813 after the Battle of River Raisin in Michigan and was sent back to Great Britain as a trophy. The design includes a shield breasted eagle, nine stars and a banner with the words “United we Stand”. The eagle clutches three arrows in one talon, and a pole with a red liberty cap in the other. The red cap is similar in style to the Phrygian cap, a symbol of French freedom, and may represent Kentucky’s early 19th century Jeffersonian-Republican political leanings and sentiments with France. |

|

Sons of Liberty The Sons of Liberty Flag was originally flown in Boston by a loosely knit association of colonists known as the Sons of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty were formed in Boston around the time of the Stamp Act protests in 1765. They would meet at a large elm tree to hold their protests. This tree became known as the Liberty Tree. They began to fly this flag whenever the leaders would want to call the townspeople together and it became known as the Sons of Liberty Flag or the Liberty Tree Flag. The flag has nine vertical red and white stripes representing the nine colonies that participated in the Stamp Act Congress of 1765. The nine colonies represented are: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and South Carolina. This flag became known as the “Rebellious Stripes” and was eventually outlawed by the British. In order to circumvent the banning of the flag, the colonists reversed the stripes to horizontal and kept using it in protests against British attempts to tax them against their will. The Sons of Liberty are best known for their actions on the evening of 16 December, 1773. That night they protested Parliament’s Tea Act by destroying a shipment of tea in an action that became known as the Boston Tea Party. |

|

Sons of the American Revolution The flag for the Sons of the American Revolution was created in 1889. The three dominant colors of the flag (blue, white, and buff) were derived from the colors of George Washington’s uniform. The logo in the center of the flag is the official insignia for the SAR. The eagle at the top of the insignia represents patriotism. The cross in the center is composed of horizontal and vertical bars. The vertical bar represents the commandment, “You shall love your God.” The horizontal bar represents the commandment, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” Each of the four limbs of the cross is in remembrance of the four cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, temperance (or moderation in all our actions), and fortitude with magnanimity and courage to serve God. Each point on the cross represents one of the beatitudes recounted for the Knights of Malta: to have spiritual contentment, to live without malice, to weep over your sins, to humble yourself at insults, to love justice, to be merciful, to be sincere and open-hearted, and to suffer persecution. The laurel wreath is derived from the French order, the Legion of Honour. The Legion of Honour was intended to fill a vacuum left by the disappearance of the old royal orders during the French Revolution and was founded on a new basis for reward – personal merit rather than birth. In the center of the insignia is the bust of George Washington. This is in remembrance of our great leader at the time of the American Revolution. Surrounding his bust are the words “Libertas et Patria,” meaning Liberty and Country. |